Synopsis

This is an unconventional monetary policy tool. It involves printing money and distributing it to the public. Imagine waking one morning to find extra cash in your account, a gift from your country’s central bank. But the concept of so-called helicopter money has been seriously debated by economists for several years, and is coming back into vogue.

With no quick escape in sight for Covid19-ravaged economies, authorities the world over are going back to the drawing board to find strategies to deal with this nightmare. Despite the trillions of dollars, euros, yen and pounds that central banks have pumped into the global financial system since the 2008 credit crisis, global economic growth is slowing once again. Helicopter money handed directly to consumers, the theory goes, would send us scurrying to the shops to spend our windfalls, boosting confidence in the economy. That increased demand would allow prices to rise again, a crucial step because a slide in prices, known as deflation, is viewed as creating the risk of extended stagnation. This renewed interest in an idea that’s almost half a century old is evidence that measures previously regarded as daring have become commonplace, repetitive — and increasingly ineffective.

What is helicopter money?

This is an unconventional monetary policy tool aimed at bringing a flagging economy back on track. It involves printing large sums of money and distributing it to the public. American economist Milton Friedman coined this term. Friedman came up with the concept of helicopter money in 1969. The Nobel Prize-winning economist envisaged a whirlybird flying over a community dropping paper money from the sky as a thought experiment to see what a never-to-be-repeated increase in the money supply would do to spending and saving. The idea was made famous by Ben Bernanke in 2002 when, as a Federal Reserve governor, he referred to it while arguing that a central bank can always stoke inflation if needed. The nickname “Helicopter Ben” stuck, even though the playbook Bernanke followed as Fed chairman during the recession that followed the financial crisis stopped short of printing money and handing it out to consumers.

In today’s debates, it’s envisaged that helicopter money would be distributed either by crediting people’s bank balances or as a tax rebate. The key is that it would come from a one-time creation of money by the central bank, rather than being borrowed by the government or coming out of existing spending.

Why is helicopter money in news now?

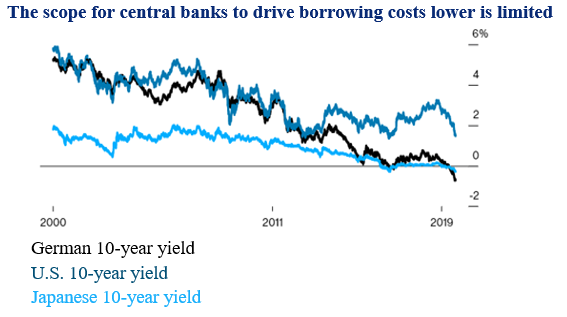

With the coronavirus-hit economy falling deeper and deeper into a chasm with each passing day, helicopter money can help to come out of this mess. The release of 5% funds from GDP by way of quantitative easing (QE). QE, a policy followed all over the world, is considered by a part of financial establishment to be the only way to deal with the situation. Helicopter money is back on the agenda because massive central bank purchases of government bonds — a policy known as quantitative easing — have already driven yields in several bond markets to record lows, so the scope for stimulating the economy by pushing borrowing costs even lower is limited. Since most governments are unwilling or unable to pursue fiscal stimulus by lowering taxes or increasing spending, there’s pressure on central banks to reach deeper into their toolkits for ever-more unconventional policy tools.

Is helicopter money the same as quantitative easing?

Quantitative easing also involves the use of printed money by central banks to buy government bonds. But not everyone views the money used in QE as helicopter money. It sure means printing money to monetize government deficits, but the government has to pay back for the assets that the central bank buys. It’s not the same as bond-buying by central banks in which bank-owned assets are swapped for new central bank reserves. Helicopter money is also different from a central bank directly financing the debt of a government.

Conclusion

Supporters of helicopter money argue that it may be less risky than quantitative easing, which has been blamed for fueling what some see as a bubble in global stock and bond markets. It is also possible that the benefits would be spread more broadly. Opponents point out that helicopter money isn’t really free. Printing more money devalues the buying power of what savers have in their accounts, in the same way that a company selling new shares dilutes the holdings of its existing stockholders. Others say helicopter money is an overly complicated substitute for the fiscal stimulus governments should be providing. There’s also the danger that helicopter money could trigger much higher inflation than the currently deemed desirable, if people thought banks or governments might get addicted to its boost. Given that nothing in economics is currently working out the way the textbooks promised, people might just save the windfall instead of spending it.